EVALUATION OF HEART RATE VARIABILITY, SOME CARDIOVASCULAR INDEXES AND NEUROTROPHIC FACTORS IN MILITARY PERSONNELS UNDER PROFESSIONAL DEPRESSIA

Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center

Institute, Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center 63 Nguyen Van Huyen, Nghia Do, Hanoi, Vietnam

Phone: +84 816499313; Email: bthuong8356@gmail.com

Main Article Content

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate selected cardiovascular physiological parameters and serum concentrations of mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor (mBDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) in 40 military personnel with depression treated at Military Hospitals 175 and 103, and in 80 controls. Methods: Heart rates and blood pressures were measured using standard clinical procedures. Heart rate variability (HRV) was analyzed from 128 consecutive beats using photoplethysmographic measurement. Serum mBDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 concentrations were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Results: In the depression group, heart rate (89.0 ± 16.6 bpm), mean arterial pressure (86.4 ± 8.4 mmHg), pulse pressure (36.8 ± 8.9 mmHg), cardiac index (2.33 ± 0.19 L·min⁻¹·m²), and total peripheral resistance (0.874 ± 0.107) differed significantly from the control group (p < 0.05). The cardiovascular adaptive potential index was 2.51 ± 0.34 units, indicating an adaptation level under stress. HRV metrics - MeanNN (0.698 ± 0.130 s), SDNN (0.026 ± 0.013 s), and CV (3.70 ± 1.58%) - were below normal reference values and lower than in controls, indicating sympathetic predominance in heart-rate regulation. Serum mBDNF (13.9 ± 7.9 ng/mL), NT-3 (59.5 ± 16.0 pg/mL), and NT-4 (59.7 ± 13.3 pg/mL) were significantly reduced compared with controls (p < 0.05). No statistically significant associations were observed between HRV indices or mBDNF, NT-3, NT-4 concentrations, and age or depression severity; pulse pressure showed a moderate inverse correlation with depression severity (r = -0.338). Conclusion: Reduced heart rate variability and decreased serum mBDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 may serve as potential biomarkers to support the diagnosis of depression.

Keywords

Heart rate variability (HRV), biomarkers, neurotrophic factors, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), neurotrophin-4 (NT-4), depression.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Highlights:

The study presents novel evidence on heart rate variability (HRV) characteristics that reflect autonomic nervous system regulation of cardiovascular function in 40 Vietnamese patients with depression.

The study also provides new data demonstrating decreased serum concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) in 40 patients with depression.

1. INTRODUCTION

Depression is a common mental disorder worldwide and a leading contributor to the global burden of disease. It affects not only mood but also cognition and behavior and may lead to the serious outcome of suicide. Each year, nearly 800,000 people die by suicide, which is the fourth leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults aged 15–29 years [1At present, the proportion of adolescent and young-adult patients with depression is rising, partly due to substance misuse and excessive video-game use. Depression may occur across all ages and occupations, particularly in jobs with exceptionally high stress. For military personnel, a stressful and potentially hazardous work environment with high professional demands may impose substantial psychophysiological strain, contributing to increased rates of depression. A meta-analysis by Yousef Moradi and colleagues reported global prevalence rates of depression of 23% in active-duty service members and 20% in veterans; notably, 11% of depressed service members reported suicidal ideation [2]. Findings from Cao Tien Duc and colleagues (2017) showed that, from 2012 to 2016, 68 service members were discharged due to depression [3]. In 2019, the prevalence of depression among 4.353 personnel in the Navy and Military Region 3 was 0.71%, spanning mild (0.50%), moderate (0.09%), and severe (0.02%) levels. The highest prevalence occurred in those aged 21–25 years (1.31%), three times that of those aged 18–20 years (0.40%) [3]. Therefore, early diagnosis and detection of depression are essential to enable timely treatment and to improve the health of service members.

Currently, the assessment and classification of depression rely primarily on psychometric scales combined with clinical symptoms, whereas evaluation of pathophysiological mechanisms using molecular biomarkers remains limited [3, 4]. Qualitative diagnoses based on these approaches depend primarily on clinician experience and on reports from patients and their families; consequently, diagnosis is not completely quantified and may lack objectivity. Accordingly, identifying alterations in biological markers as well as assessing depression-related cardiac autonomic dysfunction is necessary to clarify etiologies and pathogenesis. In addition, biomarkers can assist in subtyping depression and in evaluating treatment efficacy, offering substantial clinical utility and advancing precision medicine [5-7]. Among these, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been demonstrated to be an important biomarker in the pathophysiology of depression [8]. Decreased BDNF is closely associated with reduced synaptic plasticity and neuronal atrophy, whereas elevated BDNF is associated with neuronal survival and differentiation, consistent with neurotrophic hypotheses of depression [9, 10]. Other neurotrophic factors, such as neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) and neurotrophin-4 (NT-4), together with blood biochemical indices and hormones, have also been proposed as biomarkers for screening and diagnosing depression [10]. Nevertheless, studies quantifying such biomarkers in Vietnamese military personnel remain scarce.

Heart rate variability (HRV), the variation in the intervals between consecutive heartbeats, is regarded as an index of autonomic nervous system activity in the regulation of cardiac rhythm. Higher HRV reflects increased vagal tone [11] and better adaptability to stressors, enabling modulation of emotional responses without excessive sympathetic activation [12]. Chronic reductions in HRV indicate rigidity of autonomic responses and heightened central nervous system influence, and are frequently observed across diverse medical conditions, including depressive disorders [13]. Multiple meta-analyses have shown that patients with depression exhibit lower HRV than controls [14, 15]. HRV is also reduced in individuals at elevated risk of depression [16]. Therefore, HRV may serve as a marker linking stress responses to mental health.

Aim of the study: This study was carried out to evaluate selected cardiovascular physiological indices, the autonomic regulation of cardiovascular function, and serum concentrations of the neurotrophic factors BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 in military personnel with depression compared with controls, with the goal of providing objective, quantitative data to support more accurate screening and diagnosis.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

Inclusion criteria

Patient group: Forty service members (mean age 28.9 ± 2.1 years) diagnosed with depressive episode (F32) or recurrent depressive disorder (F33) according to ICD-10. Depression severity was assessed using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). Patients were able to understand and follow investigator instructions.

Control group: Eighty cadets from the Military Technical Officer School (mean age 22.3 ± 1.0 years), identified as fit for duty, without depression or other neuropsychiatric disorders, and without comorbidities or chronic diseases per routine unit health examinations.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with depression who had organic brain lesions or sequelae of brain/meningeal disease, epilepsy, intellectual developmental disorder, substance-induced psychotic disorder, and other psychiatric disorders were excluded.

2.2. Materials

ELISA reagents and instrumentation. Serum neurotrophic factors were quantified using Human BDNF ELISA Kit (Invitrogen, USA), NT-4 Human ELISA Kit (Invitrogen, USA) and NT-3 Human ELISA Kit (Invitrogen, USA). Optical density was read on a Multiskan Sky with Cuvette & Touch Screen microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA), together with standard reagents and ancillary equipment.

HRV and hemodynamic measurements. Heart rate variability, cardiac index, and the relative index of total peripheral vascular resistance were measured with the Ritm-MET measuring complex device (INMET LLC, Russian Federation) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [17].

2.3. Study methods and techniques

2.3.1. Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study with case–control comparison, including review of patients’ medical records was performed.

2.3.2. Blood and serum collection

Venous blood was collected in the morning by hospital staff in accordance with the Ministry of Health of Vietnam’s guidance on 55 basic nursing techniques [18]. Participants refrained from vigorous activity prior to sampling and fasted for at least 1 hour. Blood was drawn at admission, before initiation of antidepressant therapy. Venous blood was collected into clean centrifuge tubes without anticoagulant. Serum was separated by let blood to clot for 15–20 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 4°C at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes. Serum was then aliquoted and stored at −80°C. These serum samples were used to quantify BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 with the corresponding ELISA kits.

2.3.3. Quantification of BDNF, NT-3 and NT-4

Concentrations of BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 were determined using sandwich ELISAs: Human BDNF ELISA (Invitrogen, USA; sensitivity 80 pg/mL; quantitation range 0.066–16 ng/mL), NT-4 Human ELISA (Invitrogen, USA; sensitivity 2 pg/mL; quantitation range 1.4–1000 pg/mL), and NT-3 Human ELISA (Invitrogen, USA; sensitivity 4 pg/mL; quantitation range 4.12–3000 pg/mL), following the manufacturers’ protocols. Concentrations of BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 were determined using sandwich ELISAs: Human BDNF ELISA (Invitrogen, USA; sensitivity 80 pg/mL; quantitation range 0.066–16 ng/mL), NT-4 Human ELISA (Invitrogen, USA; sensitivity 2 pg/mL; quantitation range 1.4–1000 pg/mL), and NT-3 Human ELISA (Invitrogen, USA; sensitivity 4 pg/mL; quantitation range 4.12–3000 pg/mL), following the manufacturers’ protocols. Before performing ELISA, the dilution factor range was tested so that when running the sample, the protein content of the diluted sample was within the allowable limit of the kit. Serum samples for BDNF quantification were diluted 50 times (1:50 ratio, the content when diluted was within the manufacturer's recommended range of <16 ng/mL); samples for NT-3 and NT-4 quantification were diluted 2 times (1:2 ratio). Protein concentrations were multiplied 50 times and 2 times according to the dilution ratio. Standard curves were generated by plotting optical density (OD) at 450 nm versus the corresponding standard concentrations and interpolating using a second-order polynomial regression model. The resulting regression equations were used to calculate sample concentrations. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Standard curves were generated by plotting optical density (OD) at 450 nm versus the corresponding standard concentrations and interpolating using a second-order polynomial regression model. The resulting regression equations were used to calculate sample concentrations. Each assay was performed in triplicate. To ensure the reliability of the research data, each assay was performed in triplicate and a standard curve was established with each test sample. The studies were carried out in the laboratory of the Life Science Research Center, Faculty of Biology, University of Sciences, Vietnam National University, Ha Noi.

2.3.4. Measurement of anthropometrics/clinical indices and chart review

- Clinical indices (weight, height, heart rate, and blood pressure) were obtained using routine clinical procedures.

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as BMI (kg/m²) = weight (kg) / height² (m).

- Pulse pressure (PP, mmHg) = systolic blood pressure (SBP) − diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Typical values are 40–60 mmHg; values > 60 mmHg may indicate atherosclerosis and increased cardiovascular risk, whereas values < 30 mmHg may indicate reduced cardiac output, heart failure, or severe hemorrhage with risk of circulatory shock.

- Cardiac index (CI) reflects the heart’s pump function and is defined as cardiac output per body surface area; normal values are typically 2.6–4.0 L/min/m² [17].

- Relative index of total peripheral vascular resistance reflects vascular tone and overall resistance to blood flow, calculated from mean arterial pressure and cardiac output; the normal range is 0.8–1.2 arbitrary units (a.u.) [17].

- The Baevskii cardiovascular adaptation potential index (AP, R. M. Baevskii, 1979): AP = 0.011 × HR (beats/min) + 0.0148 × SBP (mmHg) + 0.008 × DBP (mmHg) + 0.014 × Age (years) + 0.009 × Weight (kg)–0.009 × Height (cm) x 0.27. Interpretation: < 2.10: adequate adaptation; 2.11–3.20: adaptation under stress; 3.21–4.30: inadequate adaptation; > 4.30: failure to adapt [11].

- Time-domain HRV indices measured by photoplethysmography included: MeanNN (s) - the mean duration of normal-to-normal (NN) interbeat intervals (R- R on ECG/peak - to - peak with PPG), expressed in seconds; SDNN (s)–the standard deviation of NN intervals. For short recordings, SDNN = 0.03–0.078 s: reflects sympathovagal balance; SDNN < 0.03 s: indicates increased sympathetic activity, whereas SDNN > 0.08 s: indicates increased parasympathetic activity. Coefficient of variation (CV, %) was calculated as CV = SDNN/MeanNN × 100%; in short recordings, CV = 5–8% indicates sympathovagal balance [17].

2.4. Data processing

Statistical analyses were conducted using StatSoft Statistica 12.0 for Windows, Microsoft Excel 2016 and Origin 8.5. Parametric data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). Differences in parametric variables were assessed with Student’s t-test. For nonparametric data, the Kruskal–Wallis test (two-sample procedure) and the Mann–Whitney U test were used. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.5. Research ethics

The project of study and research design were approved by Ethics Committees in Biomedical Research, with the following certificates: № 2907/CN-HĐĐĐ (30 Aug 2022), Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center; № 917/GCN-HĐĐĐ (24 Mar 2023), Military Hospital 175; № 57/CNChT-HĐĐĐ (14 May 2024), Military Hospital 103; protocol amendment № 5583/CN-HĐĐĐ (17 Dec 2024), Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center. All participants were explicitly informed about the study purpose and procedures and provided voluntary informed consent to participate.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Anthropometric and clinical indices

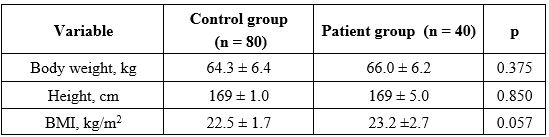

Measures such as body weight, body mass index (BMI), and blood pressure are associated with depression. The analysis of body weight, height, and BMI in the study population is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Anthropometrics and BMI of the study participants

As shown in Table 1, body weight (66.0 ± 6.2 kg; p = 0.375) and BMI (23.2 ± 2.7 kg/m², p = 0.057) were slightly higher in the depression group than in controls (64.3 ± 6.4 kg and 22.5 ± 1.7 kg/m², respectively), but the differences were not statistically significant. Height did not differ between groups (p = 0.850).

3.2. Cardiovascular physiological indices

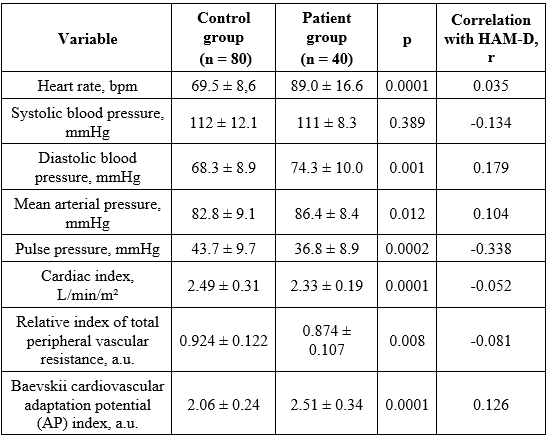

Mental health and the cardiovascular system interact in complex ways. Severe depression is regarded as an independent risk factor for several cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, and stroke [19, 20]. The analysis of heart-rate and blood-pressure characteristics in the study population is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Heart rate and blood-pressure indices in the study participants

As shown in Table 2, mean heart-rate and blood-pressure values in both groups although fell within normal ranges according to the Ministry of Health [21], these indices were higher in the depression group than in controls, with statistically significant differences (see p-values in Table 2). Specifically, mean heart rate was 89.0 ± 16.6 bpm in patients versus 69.5 ± 8.6 bpm in controls (p < 0.0001), with a very weak correlation with Hamilton depression severity (r = 0.035).

An elevated heart rate may contribute to the significantly higher diastolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure observed in patients (74.3 ± 10.0 mmHg and 86.4 ± 8.4 mmHg) compared with controls (68.3 ± 8.9 mmHg, p < 0.001; 82.8 ± 9.1 mmHg, p = 0.012). These increases showed weak positive correlations with HAM-D scores (r = 0.179 and 0.104).

Pulse pressure, cardiac index, and total peripheral vascular resistance also differed significantly between groups. Controls had a pulse pressure of 43.7 ± 9.7 mmHg (within the normal range), whereas patients had a below - normal mean pulse pressure of 36.8 ± 8.9 mmHg (p = 0.0002). Pulse pressure showed a moderate inverse correlation with HAM-D (r = -0.338). Low pulse pressure indicates reduced cardiac output, consistent with the lower cardiac index in patients (2.33 ± 0.19 vs 2.49 ± 0.31 L/min/m²; p < 0.0001) and the lower relative index of total peripheral vascular resistance (0.874 ± 0.107 vs 0.924 ± 0.122; p = 0.008). The cardiovascular adaptation potential index was higher in patients (2.51 ± 0.34 vs 2.06 ± 0.24 units; p < 0.0001), indicating adaptation under stress, and showed a weak correlation with HAM-D (r = 0.126; Table 2).

3.3. Heart rate variability indices

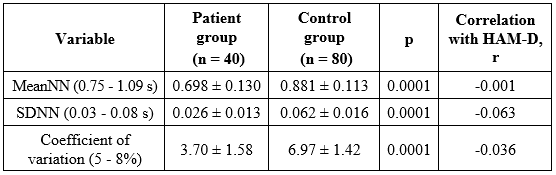

In addition to core cardiovascular measures, selected heart rate variability (HRV) indices were determined in the study population. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Time-domain HRV indices in the study participants

As shown in Table 3, HRV indices were significantly lower in the depression group than in controls–MeanNN (0.698 ± 0.130 s vs 0.881 ± 0.113 s), SDNN (0.026 ± 0.013 s vs 0.062 ± 0.016 s), and CV (3.70 ± 1.58% vs 6.97 ± 1.42%; all p < 0.0001) - and were below typical short-term reference values. These reductions indicate autonomic imbalance with sympathetic predominance in patients. Correlations with HAM-D scores were very weak, even close to zero (|r| ≤ 0.063).

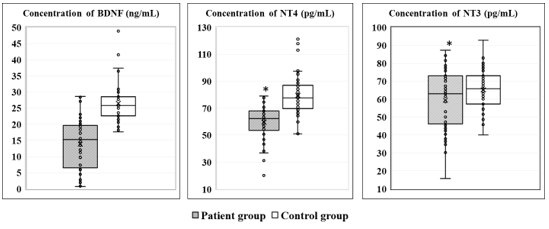

3.3. Serum concentrations of neurotrophic factors mBDNF, NT-3 and NT-4

The serum concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and Neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) measured in peripheral venous blood from patients with depression and controls are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Serum concentrations of BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4 in the study participants. (*p < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference between groups.)

As shown in Figure 1, serum concentrations of BDNF (13.9 ± 7.9 ng/mL), NT-3 (59.5 ± 16.0 pg/mL) and NT-4 (59.7 ± 13,.3 pg/mL) in patients were markedly lower than in controls (26.5 ± 6.1 ng/mL, p < 0.0001; 65.2 ± 10.7 pg/mL, p < 0.0001; 79.5 ± 13.9 pg/mL, p = 0.03, respectively). The corresponding odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were: BDNF: OR = 17.57; 95% CI 5.35 – 57.62; p < 0.001; NT-3: OR = 14.54; 95% CI 5.15 – 41.05; p < 0.001 and NT-4: OR = 1.20; 95% CI 0.64 – 2.87. Serum BDNF, NT-4, and NT-3 showed weak correlations with age (r = 0.106, -0.189, and -0.159, respectively) and with depression severity on the HAM-D (r = 0.290, -0.393, and -0,286, respectively).

4. DISCUSSION

In recent years, the association between body weight and depression has attracted considerable attention, yielding heterogeneous findings. Araghi M.H. and colleagues, in a study of 270 patients, reported more pronounced depressive symptoms among individuals who were overweight or obese [22]. The authors also identified robust positive correlations among sleep duration and quality, anxiety, stress, and depression in patients with severe obesity. Sleep deprivation may contribute to weight gain[1] [A2] through increased levels of hormones such as ghrelin and reduced levels of adipose-derived hormones such as leptin, either alone or in combination, thereby promoting weight gain [22]. Other studies have described a U-shaped relationship between Asian-specific BMI categories (18.5, 23, 25, and 30 kg/m²) and the severity of depressive symptoms in adults [23, 24]. Both underweight and severe obesity were associated with a higher risk of depression; the BMI ranges associated with the lowest likelihood of depression were 18.5 - 25 kg/m² in women and 23-25 kg/m² in men [23]. In the present study, body weight did not differ significantly between patients and controls, whereas BMI was higher in the depression group (p = 0.057); the correlation between BMI and Hamilton depression score was weak (r = 0.031). In addition, a prior publication from this project showed statistically significant increases in cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, and glucose in patients with depression relative to controls [25]. Depression may increase appetite and elevate circulating cortisol, thereby reducing glucose tolerance, increasing blood pressure, promoting fat accumulation, and ultimately contributing to metabolic syndrome [10][3] [A4] . Taken together, our findings support an interactions between depression, BMI, and several metabolic processes (serotonin and lipid metabolism and glucose tolerance). However, the mechanisms underlying these relationships warrant further investigation in larger samples.

The relationships between mental disorders and elevated heart rate, high blood pressure, and hypertension have been examined by many authors, with varying results. The higher heart rate in our patient group is consistent with Celine Koch and colleagues’ meta-analysis of 21 studies including 2.250 patients with depression and 982 controls, which found increased heart rate across all depressed patients [14]. By contrast, Schaare et al., analyzing data from 502.494 individuals at baseline and 47.933 at a 9-year follow-up, observed that higher systolic blood pressure was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, better perceived health, and lower emotion-related brain activity [19]. Meanwhile, Correll C.U. and colleagues’ meta-analysis of 92 studies reported that hypertension and affective disorders, including depression, frequently co-occur [20]. Diastolic blood pressure—the arterial pressure during cardiac diastole-plays a crucial role in delivering oxygenated blood to the myocardium via the coronary arteries and is closely linked to coronary artery disease. Elevated diastolic pressure, particularly when systolic pressure remains normal, may increase the risk of coronary and other cardiovascular diseases. Depression and stress can activate the sympathetic nervous system, increasing secretion of adrenaline and cortisol and thereby raising blood pressure. Correll et al. also found that individuals with major depressive disorder have an elevated risk of coronary artery disease [20].

The cardiovascular system is core element of physiological adaptation to environmental factors; therefore, circulatory function (or adaptive capacity) can be regarded as an important indicator of organism-wide adaptive responses [11]. In this study, the cardiovascular adaptation potential (AP) index was 2.51 ± 0.34 a.u. in patients consistent with adaptation under stress to internal and external environmental changes whereas adaptation was normal in controls.

Reduced heart rate variability (HRV) in the depression group reflects sympathovagal imbalance with sympathetic predominance [11, 12]. Hyperactivity of the sympathetic system may also influence social interaction networks and reduce social engagement in patients with depression, ultimately manifesting as emotional symptoms such as anxiety, restlessness, agitation, irritability, low mood, and sleep and appetite disturbances [26]. The close association between HRV and depression may originate from shared neural regulatory regions, most notably the insular cortex. HRV biofeedback training that targets these circuits has been shown to improve certain depressive symptoms [26]. These observations further support HRV as a potential physiological marker for predicting and diagnostics of depression, as well as a therapeutic target to ameliorate the disorder.

The decreased serum concentrations of neurotrophic factors observed in our patients align with many prior reports and reinforce the role of BDNF in the pathophysiology of depression [6-10, 27]. According to the synthesis by Castrén and Monteggia [9], serum or plasma BDNF levels are reduced in patients with depression and return to baseline following successful treatment with antidepressant medication or electroconvulsive therapy, but not after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or vagus-nerve stimulation. Using ELISA in 90 patients with major depressive disorder and 96 controls, Liying Lin and colleagues found that serum mBDNF was significantly lower in patients with severe symptoms than in those with moderate symptoms (p < 0.05) [27]. Serum mBDNF was also significantly lower in non-medicated patients than in those receiving antidepressants (p < 0.01). Serum mBDNF provided good diagnostic performance for major depressive disorder, with sensitivity and specificity of approximately 80–83%; a potential diagnostic cut-off of 12.4 ng/mL has been proposed [27].

Beyond BDNF, the roles of other neurotrophic factors such as NT-3 and NT-4 in the pathogenesis of certain neurodegenerative diseases and their therapeutic potential have been widely investigated. In our study, NT-3 and NT-4 were both decreased in patients relative to controls (p < 0.05). These findings are in line with the report by Sheldrick and colleagues [28], who assessed post-mortem brain tissue from 21 individuals (7 patients and 14 controls). Measuring mBDNF and NT-3 across multiple brain regions (frontal lobe, cingulate gyrus, thalamus, hippocampus, cortex, and caudate nucleus), they observed significant increases in BDNF (parietal cortex) and NT-3 (parietal, temporal, and occipital cortices; cingulate gyrus; thalamus; neocortex; and caudate) in patients with severe depression who had received antidepressants, compared with untreated patients and controls. They also found significantly decreased NT-3 in the parietal cortex of untreated patients with severe depression compared with healthy controls [28]. In contrast, Wysokiński et al., studying 33 patients and 27 healthy individuals, found no such differences [29]. Arabska and colleagues reported elevated NT-3 in patients with schizophrenia with comorbid depression (202.61 ± 258.76 pg/mL) compared with patients with schizophrenia without depression and no predominant negative symptoms, those with schizophrenia without depression with predominant negative symptoms (83.79 ± 215.75 pg/mL), and controls (36.47 ± 73.84 pg/mL) (p = 0.016) [30]. Overall, NT-3 and NT-4 are thought to participate in neurobiological processes related to depression. Their potential antidepressant effects may be mediated through actions on monoaminergic neurotransmission (serotonin and noradrenaline) and modulation of synaptic plasticity [30]. Further focused studies are needed to clarify the roles of NT-3 and NT-4.

5. CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated statistically significant differences between patients with depression and healthy humans (controls) in circulatory physiological indices - heart rate, diastolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, cardiac index, relative total peripheral vascular resistance and the Baevskii cardiovascular adaptation potential, as well as in cardiac autonomic indices (MeanNN, SDNN, CV) and in serum concentrations of the neurotrophic factors BDNF, NT-3 and NT-4. However, within the 40 patient cohort of study, age and depression severity were not associated with differences in neurotrophic factor concentrations. These findings support the potential use of combined biochemical and physiological autonomic measures to aid the diagnosis of depressive disorders in Vietnam.

Study Limitations

This study was conducted on a relatively small sample size. There was also age heterogeneity between the patient and control groups. This was done to facilitate sample selection given the limited sample size, as the entire sample consisted of soldiers with depression admitted to hospitals for treatment.

Acknowledgments: This article is funded by the General Department of Logistics/ Ministry of National Defense and Joint Vietnam - Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center. Sample collection procedures were carried out with the assistance of physicians and nurses at Military Hospital 175 and Military Hospital 103. All patients studied volunteered to participate.

Statement on the use of Generative AI: The authors affirm that no generative AI tools were used to create or modify the scientific content of this manuscript. All analyses, interpretations, and conclusions are entirely the work of the authors.

Author contributions: Pham Thi Bich: Blood-sample quantification, data analysis, manuscript writing and revision; Vu Thi Thu: Manuscript revision, conclusions; Tran Duc Khanh: Quantitative assays, data processing; Ngo Thi Hai Yen: Materials and methods, manuscript writing and revision; Nguyen Van Ca; Dinh Vu Trong Ninh; Dang Tran Khang; Do Xuan Tinh; Nguyen Thi Tam: Data collection, conceptualization, methodology; Luong Thi Mo: Blood-sample collection and processing, methodology; Tran Thi Nhai; Le Van Quang; Nguyen Mau Thach; Nguyen Hong Quang; Nguyen Thi Thuy Linh: data collection and processing; Bui Thi Huong: Study design and organization; manuscript writing and revision; results and conclusions.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

2. Y. Moradi , B. Dowran, and M. Sepandi, The global prevalence of depression, suicide ideation, and attempts in the military forces: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of cross sectional studies, BMC Psychiatry, Oct 15, 21 (1), 510, 2021. DOI: 10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2

3. Cao Tien Duc et al, Results of 5 years of assessment at the medical assessment council of mental illness of the Ministry of National Defense, Journal of Military Pharmaco-medicine, N. 6, 2017.

4. Cao Tien Duc, Bui Quang Huy and Huynh Ngoc Lang, Study on the rate of major depressive disorder in some military units, Journal of Military Pharmaco-medicine, N. 8, 2019.

5. I. Grahek, A. Shenhav, S. Musslick, R. M. Krebs and E. H. W. Koster, Motivation and cognitive control in depression, Neurosci Biobehav Rev., Vol. 102, pp. 371-381, Jul, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.011

6. S. G. Kang, S. E. Cho, Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Predicting Treatment Response and Recurrence of Major Depressive Disorder, Int J Mol Sci, Vol. 21, No. 6, Mar 20, pp. 2148, 2020. DOI: 10.3390/ijms21062148

7. Z. Li, M. Ruan, J. Chen and Y. Fang, Major Depressive Disorder: Advances in Neuroscience Research and Translational Applications, Neurosci. Bull, Vol. 37, No. 6, Jun, pp. 863-880, 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s12264-021-00638-3

8. B.P. Carniel, N.S. da Rocha, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and inflammatory markers: Perspectives for the management of depression, Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 108, Jun 8, p. 110151, 2021. DOI: 0.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110151

9. E. Castrén, L. M. Monteggia, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling in Depression and Antidepressant Action, Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 90, No. 2, Jul 15, pp. 128-136, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.05.008

10. B. J. Lee, Association of depressive disorder with biochemical and anthropometric indices in adult men and women, Scientific Reports, Vol. 11, No.1, p. 13596, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-93103-0

11. R. M. Baevsky, Analysis of Heart Rate Variability in Space Medicine, Human Physiology, Vol. 28, pp. 202-213, 2002. DOI: 10.1023/A:1014866501535

12. L.L. Hourani et al., Mental health, stress, and resilience correlates of heart rate variability among military reservists, guardsmen, and first responders, Physiology & Behavior, Vol. 214, Feb. 1, p. 112734, 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112734

13. S. Galin, H. Keren, The Predictive Potential of Heart Rate Variability for Depression, Neuroscience, Vol. 546, May 14, pp. 88-103, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112734

14. C. Koch, M. Wilhelm, S. Salzmann, W. Rief and F. Euteneuer, A meta-analysis of heart rate variability in major depression, Psychological Medicine, Vol. 49, No. 12, Sep., pp. 1948–1957, 2019. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291719001351

15. D. Donnelly, E. Georgiadis and N. Stavrou, A meta-analysis investigating the outcomes and correlation between heart rate variability biofeedback training on depressive symptoms and heart rate variability outcomes versus standard treatment in comorbid adult populations, Acta Biomed, Vol. 94, No. 4, Fug. 3, pp. e2023214, 2023. DOI: 10.23750/abm.v94i4.14305

16. T. Moretta, S. Messerotti Benvenuti, Early indicators of vulnerability to depression: The role of rumination and heart rate variability, Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 312, Sep. 1, pp. 217-224, 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.049

17. A.A. Shvaichenko, V.A. Linok and V.A. Sakovich, New opportunities to ensure the safety of professional activities of the contingent of the Missile Strategic Forces (MSF), Military Thought, Vol.11, pp. 35-38, 2009.

18. Do Dinh Xuan, Tran Thi Thuan, Practical guide to 55 basic nursing techniques, Vietnam Education Publishing House Limited Company, Volume 2, 2010, pp. 285-287,

19. H. L. Schaare et al, Associations between mental health, blood pressure and the development of hypertension, Nature Communications, Vol. 14, No. 1, Apr 7, p. 1953, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-37579-6

20. C.U. Correll et al., Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls, World Psychiatry. Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 163–180, 2017. DOI: 10.1002/wps.20420

21. Ministry of Health (Vietnam) portal, https://moh.gov.vn/chuong-trinh-muc-tieu-quoc-gia/-/asset_publisher/7ng11fEWgASC/content/tang-huyet-ap-nhan-biet-ieu-tri-va-phong-ngua?inheritRedirect=false.

22. M. H. Araghi et al, The complex associations among sleep quality, anxiety-depression, and quality of life in patients with extreme obesity, Sleep, Vol. 201336, No. 12, Dec. 1, pp. 1859-1865. DOI: 10.5665/sleep.3216

23. J. W. Noh, Y. D. Kwon, J. Park and J. Kim, Body mass index and depressive symptoms in middle aged and older adults, BMC Public Health, Vol. 15, Mar 31, p. 310, 2015. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-015-1663-z

24. J. H. Lee et al, U-shaped relationship between depression and body mass index in the Korean adults, European Psychiatry, Vol. 45, Sep., pp. 72-80, 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.05.025

25. Pham Thi Bich et al, Evaluating several biological indicatorsin depressed vietnamese soldiers, Vietnam Journal of Physiology, Vol, 28, N. 2, pp.104 -114, 2024. DOI: 10.54928/vjop.v28i1

26. S. Galin, H. Keren, The Predictive Potential of Heart Rate Variability for Depression, Neuroscience, Vol. 546, May 14, pp. 88-103, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.03.013

27. L. Lin, X. Y. Fu, X. F. Zhou, D. Liu, L. Bobrovskaya and L. Zhou, Analysis of blood mature BDNF and proBDNF in mood disorders with specific ELISA assays, Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 133, Jan., pp. 166-173, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.021

28. A. Sheldrick et al., Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin 3 (NT3) levels in post-mortem brain tissue from patients with depression compared to healthy individuals - a proof of concept study, European Psychiatry, Vol. 46, Oct., pp. 65-71, 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.06.009

29. A. Wysokiński, Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) in depressed patients with schizophrenia, Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 70, No. 4, Nov 7, pp. 267-271, 2016. DOI: 10.3109/08039488.2015.1087592

30. J. Arabska, A. Lucka, D. Strzelecki and A. Wysokiński, In schizophrenia serum level of neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) is increased only if depressive symptoms are present, Neuroscience Letters, Vol. 684, Sep 25, pp. 152-155, 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.08.005