DEVELOPMENT OF MOLECULARLY IMPRINTED POLYMERS FOR THE SELECTIVE ADSORPTION AND PRECONCENTRATION OF AURAMINE O DYE

Faculty of Chemistry, University of Science, Vietnam National University, Ha Noi

Faculty of Chemistry, University of Science, Vietnam National University, Ha Noi

Email: m.t.n.pham@gmail.com

Main Article Content

Abstract

For the selective adsorption and enrichment of Auramine O, this study effectively synthesized and characterized molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) via precipitation polymerization of ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) as a cross-linker and methacrylic acid (MAA) as a functional monomer. SEM, EDS and FT-IR characterization verified the formation of imprinted cavities designed for Auramine O recognition. A mesoporous structure with an average pore diameter of 7.334 nm, a large pore volume (0.6166 cm³ g⁻¹), and a high specific surface area (336.31 m² g⁻¹) were determined by nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis, enabling improved adsorption performance. Adsorption studies demonstrated a maximum capacity (qmax) of 125.521 mg g⁻¹, with high selectivity toward Auramine O relative to structurally similar dyes and minimal suppression from electrolytes. Additionally, by optimizing the extraction process, an enrichment factor of 50 was achieved. The MIPs demonstrated remarkable reusability by retaining the high adsorption and desorption efficiencies over up to five cycles. Applying the proposed method on bamboo shoot samples, the recoveries ranged from 78.45% to 96.87%, with relative standard deviations below 7%. These results exhibit the method's suitability and robustness for the sensitive, selective detection of prohibited dyes in complex food matrices, highlighting its potential for routine food safety monitoring and regulatory compliance.

Keywords

Molecularly imprinted polymers, Auramine O quantification, selective adsorption, efficient enrichment, bambo shoots analysis.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Highlights:

Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) were synthesized via precipitation polymerization, forming selective recognition sites for Auramine O with high structural stability and adsorption efficiency.

The MIPs showed a maximum adsorption capacity of 125.521 mg g⁻¹ and a selectivity factor (IF) of 2.77, while maintaining strong reusability over multiple adsorption - desorption cycles.

Application to bamboo shoot samples yielded high recovery rates (78.45% - 96.87%) with RSDs below 7% and up to 50-fold enrichment, confirming their effectiveness for trace-level detection in complex food matrices.

These results demonstrate the potential of the developed MIPs for integration into solid-phase extraction and adaptation to advanced analytical platforms for food safety and environmental monitoring.

1. INTRODUCTION

Auramine O is a cationic dye of the diarylmethane class with abundant applications in the textile, papermaking, tanning, printing, and also in the biological and medical industries [1, 2]. However, the persistence of this compound in the environment is considered to pose serious risks. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the dye compound is classified as Group 2B which indicates possible carcinogenicity to humans [3-5]. Furthermore, Michler's ketone, an extremely toxic mutagenic compound, is often detected in commercial Auramine O dye [6, 7]. Acknowledging the extreme toxicity of Auramine O and the potential risk of widespread misuse, it is prohibited as a food additive across countries and regions, including Vietnam [8].

However, in recent years, an increasing number of violations have been reported, in which Auramine O was illegally detected in pickled bamboo shoots and durians presented in domestic markets[9]. Despite being stained with a high concentration of Auramine O to preserve color, bamboo shoot samples may retain only trace amounts of the dye, making detection and quantification challenging. This immediately raises concerns in public and highlights the urgent need of developing methods for trace detection of Auramine O in complex food matrices[10, 11]. In terms of constructing efficient techniques, sample preparation serves a crucial role in defining precision and sensitivity.

Solid phase extraction (SPE) has been used as an effective, highly applicable and compatible technique for advanced analytical instruments like HPLC, LC-MS [12, 13]. Hence, synthesizing appropriate adsorbent materials for extract columns is an essential step for enhancing SPE performance. In recent years, many adsorbents have been synthesized and studied, including activated carbon (AC) [14], HPD300 resin, halloysite nanotubes (HNTs)[15], and hybrid MOF/COF material [16]. Some nanostructured composites like ZnS:Cu/AC and adsorbents derived from carboxymethyl cellulose exhibited high adsorption capacity, attributed to their enhanced surface area and abundant specific binding sites [17]. Nevertheless, a common drawback of these adsorbents can be witnessed is their insufficient molecular selectivity, which may undermine the performance in intricate matrices. Additionally, most commercial adsorbents exhibit poor reusability, which may lead to secondary waste and ultimately have a negative impact on the environment.

To overcome these challenges, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) as a promising type of material have emerged for selective extraction and preconcentration [18, 19]. MIPs are synthetic polymers developed for excellent molecular recognition sites toward a specific target molecule [20]. MIPs are advantageous because of the ease in preparation, high specific mechanical, thermal stability, and reusability[21-24]. This characteristic makes MIPs useful for the selective adsorption, removal, and concentration of Auramine O even in complicated sample matrices.

In this study, molecularly imprinted polymers for adsorption of Auramine O were synthesized via precipitation polymerization with methacrylic acid (MAA) as a functional monomer and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) as a cross-linker. The conditions for synthesis and adsorption of MIPs were studied and optimized to improve selective enrichment performance. The prepared MIPs was then applied in the solid-phase extraction of Auramine O from pickled bamboo shoot samples and consequently quantified by UV-Vis molecular absorption spectrophotometry. This spectroscopic method achieved enhanced sensitivity and selectivity with assistance from the integration of MIPs in the sample preparation, while also improving the accuracy and reliability of trace Auramine O detection in food matrices.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and Instrumentations

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) or Merck (Germany). These include Auramine O (99%), methacrylic acid (MAA, 99%), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, 98%), azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN; 98%), acetonitrile (ACN; 99.9%), methanol (MeOH, 99%), ethanol (EtOH, 99%), and glacial acetic acid (99.9%). Several dyes and interfering compounds were also used for selectivity and interference studies, including Malachite Green (99%), Chrysodine G (99%), Tartrazine (99%), and Leuco Malachite Green (99%). Inorganic salts such as sodium chloride (NaCl, 99%), magnesium chloride (MgCl₂, 99%), potassium chloride (KCl, 99%), and calcium chloride (CaCl₂, 99%) were also employed. Deionized water was used throughout all experiments.

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1601, Shimadzu) was used for quantifying Auramine O and evaluating adsorption/desorption. The MIPs synthesis was conducted with a magnetic stirrer (C-MAG HS 7, IKA). Adsorption studies were supported by a refrigerated centrifuge (Eppendorf 5420) and a horizontal shaker (SHR-1D).

2.2. Synthesis of adsorbent materials

Auramine O – molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) was synthesized via precipitation polymerization. In this research, the molar ratio of Auramine O:MAA:EGDMA for MIPs synthesis is 1.2:1:4. Briefly, 1.0 mmol Auramine O (500 ppm) and 1.2 mmol MAA (functional monomer) were dissolved in 40.0 mL porogenic solvent of ACN:MeOH (3:1, v/v) and stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then, 4.0 mmol EGDMA (cross-linker) and 10.0 mg AIBN (initiator) were added, the mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 18 h. The resulting polymer after polymerization was washed repeatedly by EtOH/HOAc (8:2, v:v) and centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 15 mins in order to remove residual template and monomers. This elution process was monitored by measuring absorbance of the eluting solution at 431 nm by UV-Vis spectroscopy until no signal was detected, confirming the complete removal of Auramine O in the polymer network. The dried MIPs were obtained by heating at 100°C for 8 h.

Non-imprinted polymers (NIPs) were prepared under similar conditions without Auramine O as template molecules.

2.3. Adsorption Study

The adsorption behavior of the MIPs and NIPs was evaluated using a static adsorption method. In each experiment, an identified amount of sorbent materials (0.1–3 mg mL-1) were added to Auramine O solutions with initial concentrations (C₀) ranging from 5 to 450 mg L-1. All of the working solution were adjusted to pH 6.5, then were gently shaken at room temperature for 1 to 90 minutes to reach adsorption equilibrium. Consequently, the solutions were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 15 minutes to separate the solid material from the solution. The residual Auramine O concentration (Ce) was measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometry at maximum adsorbance wavelength of 431 nm. Based on these values, the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qₑ), removal efficiency (H%), and imprinting factor (IF) were calculated using established equations.

C₀ and Cₑ (mg L⁻¹) represents the initial and equilibrium concentrations of Auramine O, respectively, V (L) is the volume of the adsorption solution, and m (g) is the mass of the polymer. qₘ MIP and qₘ NIP (mg g⁻¹) refer to the maximum adsorption capacities of MIPs and NIP, respectively.

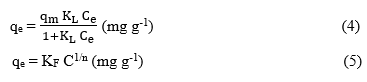

Two isothermal adsorption models, Langmuir and Freundlich, were conducted to perform regression analysis of the adsorption isotherms of Auramine O onto the MIPs material [25]. The nonlinear forms of these models are expressed through the following equations.

Here, qₑ and qₘ represent the equilibrium adsorption capacity and the maximum adsorption capacity (mg g⁻¹), respectively. The Langmuir constant KL (L mg⁻¹) and the Freundlich constant KF (mg g⁻¹) are both indicators of adsorption strength [26, 27]. In the Freundlich isotherm model, the parameter n reflects the degree of surface heterogeneity and offers insights into the distribution of adsorbed molecules on the absorbent surface. This model describes multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and is particularly useful for describing non-ideal adsorption systems.

2.4. Desorption Study

This research evaluated the desorption efficiency and reusability of molecularly imprinted polymer (MIPs) materials through static adsorption experiments. The desorption of Auramine O from the MIPs was optimized by examining the effects of different solvent systems, including ethanol/acetic acid (EtOH:HOAc), acetonitrile/ethanol (ACN:EtOH), and water/acetic acid (H₂O:HOAc), at two volume ratios (8:2 and 2:8, v/v) to determine the most effective desorption condition. After adsorption, MIPs particles were separated from the solution and then used in the desorption process. The effects of solvent volume (1 to 25 mL) and desorption time (1 to 30 minutes) were carefully examined to optimize the process.

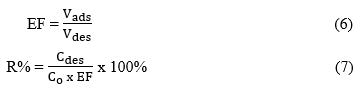

To evaluate the material’s long-term reusability, five consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles were conducted. The desorption yield was quantified using the enrichment factor (EF) and the desorption percentage (R%), calculated based on the following formulas:

Vdes is the final volume of the desorption solution (mL), Vads is the initial volume of the adsorption solution (mL), Cdes is the concentration of Auramine O recovered after desorption (mg L⁻¹), and C0 is the initial concentration of Auramine O before adsorption (mg L⁻¹).

2.5. Sample preparation

Fresh bamboo shoot samples were obtained in domestic markets in Hanoi, Vietnam. For preparing the extracted solution, 2.0 g of each sample was sufficiently washed by DI water and grinded in a blender. Subsequently, the solid sample underwent sonication extraction combining with stirring in 10.0 mL solvent system of EtOH:H2O (7:3, v/v) acidified to pH 3 by hydrochloric acid for 2 hours at 40 0C.The extracted solution then was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm and 4 0C for 10 minutes to remove residual particulates. Following this, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 um PTFE syringe filter, obtaining the final extract which was stored at 4 0C for further preconcentration and UV-Vis analysis at 431 nm.

MIPs was applied to selectively preconcentrate Auramine O from aqueous samples. Firstly, 20 mg of MIPs were dispersed in 50.0 mL of sample solution which was stirred for 40 minutes at room temperature. After centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 15 minutes, Auramine O was eluted with 1 mL of ethanol:acetic acid (8:2 v/v) solution. Finally, the eluate was analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy.

3. REQUEST AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Physicochemical Properties

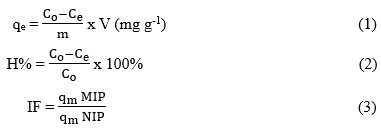

The surface morphology of both synthesized MIPs and NIPs material was studied with SEM analysis, highlighting differences. Notably, the NIP material is made of particles which are rough and irregular in shape which in turn dense and form a compact block as shown in Figure 1A. However, Figure 1B indicates the MIPs material which has a highly porous structure with more homogenous particles ranging from 150 to 250 nm. Such porosity is due to the imprinting of the molecules with appropriate added functional monomer to cross-linker ratio of 1:3 for the formation of binding cavities for Auramine O [28, 29]. After template molecules are removed from the polymer structure by elution, selective cavities form during polymer template removal which increases specific surface area and porosity, which supports retention to a far greater extent [28, 29]. Thus, the adsorption performance of MIP materials surpasses that of NIP materials, which do not possess such pores.

Figure 1. (A) SEM image of NIPs; (B) SEM image of MIPs; (C) EDS data and (D) FT-IR spectrum of NIPs and MIPs

EDS spectroscopy of both MIP and NIP materials (Figure 1C) indicate the presence of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) with characteristic peak values of 0.27 keV and 0.52 keV, respectively. For the MIP material, the atomic proportion of carbon and oxygen are 82.88% and 17.12% while it is 85.01% carbon and 14.99% oxygen in NIPs. The increase of oxygen that is present in MIP as compared with NIPs is most likely due to the imprinting process, which tends to increase oxygen containing functional groups that are requisite for developing recognition sites [30], [31], [32], [33]. The FT-IR characterization (Figure 1D) confirms the copolymerization between MAA and EGDMA showing absorption bands at 3500 cm⁻¹, 1720 cm⁻¹ and 1635 cm⁻¹ attributed to hydroxyl (O-H), carbonyl (C=O) and alkene or conjugated system (C=C).

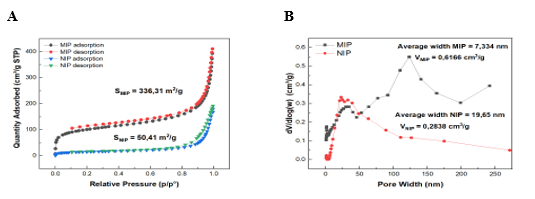

Figure 2. (A) Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm plots of MIPs and NIPs at 77 K; (B) Pore size distribution data of MIPs and NIPs.

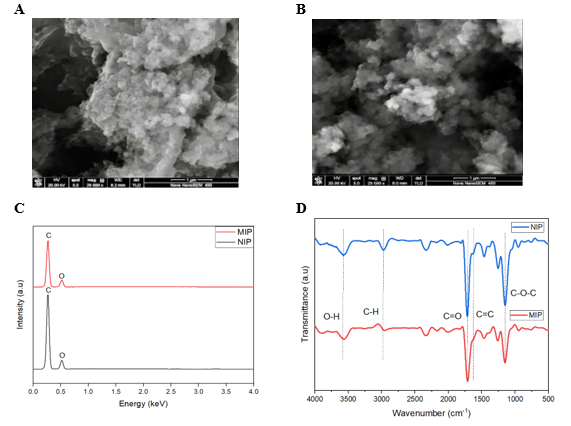

The nitrogen adsorption isotherm model (Figure 2A) demonstrates significant differences in terms of adsorption capacity and structural design between MIPs and NIPs. The MIPs material obtained an excellent specific surface area of 336.31 m2 g-1, surpassing that of NIPs (50.41 m2 g-1). This data highlights the importance of molecular imprinting in designing specific binding cavities for Auramine O adsorption. As far as the pore characteristics are concerned in Figure 2B, MIPs suggested the mesoporous structure with an average pore diameter of 7.334 nm and large pore volume of 0.6166 cm3 g-1. In contrast, the NIPs material has wider pore width (19.65 nm) and very low pore volume (0.2838 cm3 g-1), suggesting limitations in terms of adsorption capacity and selectivity. With a well-tailored microstructure, MIPs demonstrate a uniform polymer network [34, 35], which is effective for retaining Auramine O. Based on the mentioned parameters, it can be claimed that molecular imprinting is remarkably crucial in the synthesis of the polymeric material, structurally and chemically suitable for interacting with target molecules. Overall, enhanced adsorption efficiency and selectivity in MIPs can be observed in comparison with non-imprinted material.

3.2. Adsorption properties

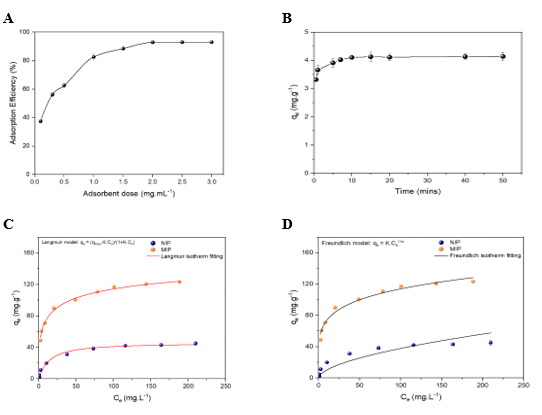

The MIPs adsorbent dose was thoroughly investigated (Figure 3A) by using a range of 0.1 - 3.0 mg mL-1 for the adsorption of 10.0 mL of Auramine O stock solution 10.0 ppm in 30 minutes. It can be observed that the adsorption efficiency sharply increased at a lower content of MIPs and became saturated when applying a concentration of 2.0 mg mL-1, obtaining an optimized value of 94.09%. Due to the fact that specific binding sites are considered completely occupied at this material content, it was chosen for further experiments.

Figure 3. (A) Study of optimized adsorbent concentration; (B) Adsorption duration study; (C) Langmuir isotherm adsorption model and (D) Freundlich isotherm adsorption model of MIPs and NIPs with Auramine O as template (n = 3).

The effect of contact time on the adsorption capacity of MIPs (Figure 3B) was investigated systematically to determine the optimal adsorption time. The results indicate that the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) rose continuously during the early phase, i.e., from 0 to 20 minutes, suggesting that the adsorption sites on the material surface were filled progressively with Auramine O molecules. This rapid uptake is because there was an abundant presence of active sites for binding in the early stages of contact. The adsorption process attained equilibrium at 20 minutes, which means the respective sites were saturated. This proves that most of the accessible and high-affinity sites were occupied within this period. Therefore, 20 minutes of contact time was selected as the optimal adsorption time and applied in all the subsequent experiments to ensure proper contact between the adsorbent and the analyte.

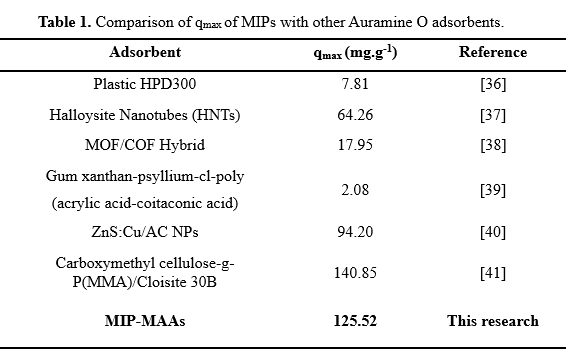

To determine the appropriate isotherm adsorption model, the relationship between equilibrium concentration (Ce) and equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) was deduced in Figure 3C and Figure 3D. In this study, adsorption experiments was conducted applying 2.0 mg mL-1 of either MIPs or NIPs for 10.0 mL solution with various concentrations of Auramine O (measurement conditions: pH 6.5, 25 oC, 20 minutes). For both MIPs and NIPs, the Langmuir isotherm model demonstrates a higher correlation with obtained data than the Freundlich model, with R2 values of the Langmuir model being 0.9932 and 0.9905 in comparison with 0.9815 and 0.9282 of the Freundlich model, respectively. In the Langmuir isotherm model, adsorption constant KL is a parameter of binding affinity between adsorbent and target molecule. Particularly, KL of MIPs and NIPs was determined as 2.857 and 0.424 L mg-1, with higher binding capacity between MIPs and Auramine O. Notably, maximum adsorption capacity qmax of MIPs material of 125.521 mg g-1 was determined, while NIPs only achieve a value of 45.897 mg g-1. With this data, the imprinted factor of 2.77 demonstrates outstanding adsorption efficiency and selectivity of MIPs, suitable for other studies of imprinted polymers. In comparison with other adsorbents listed in Table 1, MIPs synthesized from MAA and EGDMA highlight a significantly enhanced adsorption efficiency among all.

For the pH condition of working solutions, pH 6.5 was chosen as the optimum condition for chemical interaction of Auramine O and the functional groups of MIPs. In particular, Auramine O is a basic amine dye with pKa1 of 9.8, staying as a positive molecule at working pH condition. Meanwhile, most functional groups of MIPs are carboxyl groups due to the use of MAA as monomer, remaining negatively charged at pH 6.5 which promotes stable ionic interaction of MIPs and Auramine O. Both chemical optimization by pH condition and enhanced structural design of specific binding cavities in MIPs resulted in excellent adsorption capacity for Auramine O. Furthermore, the use of pH 6.5 for the Auramine O removal drives significant impacts for environmental sampling and monitoring due to the fact that most samples consist pH of slightly acidic to neutral.

3.3. Desorption properties and enrichment capability

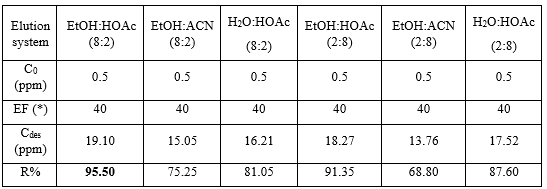

Different solvent systems were applied for the elution of Auramine O from MIPs material which are shown in Table 2. Above all, the ethanol:acetic acid (8:2 v/v) solution achieved the highest desorption efficiency with R = 95.5%, in which ethanol provided polarity for the system for favourable mass transfer, whereas acetic acid weakens the hydrogen bonding and ionic bonding between Auramine O and MIPs [42]. The use of this solvent system leads to the sufficient elution of analytes from specific adsorption sites while intact the polymeric structure. Despite the fact that Auramine O is highly soluble in water alone, desorption efficiency of using ethanol:acetic acid is slightly higher than that of applying water:acetic acid attributed to enhanced diffusion of ethanol in a moderate hydrophobic polymer network. On the other hand, the ethanol:acetonitrile system lacks ionic strength to destabilize interaction between Auramine O and MIPs due to the absence of acetic acid, resulting in reduced efficiency [43]. Therefore, the EtOH:HOAc (8:2 v/v) solution which achieved the highest desorption efficiency was further applied in desorption experiments.

Table 2. Study of elution systems with different volume ratios (n = 3).

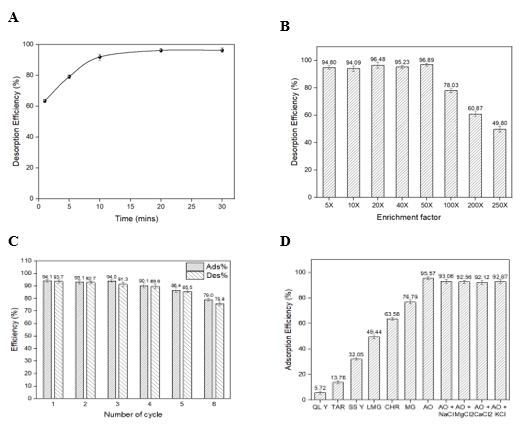

(*) EF: Enrichment factor

An investigation was conducted to optimize the desorption duration using the solvent system of ethanol:acetic acid (8:2 v/v) in the range of 0 - 30 minutes (Figure 4A). It can be observed that desorption efficiency gradually increases during the first 20 minutes and reaches the highest value of 96.08%. Hence, a duration of 20 minutes was chosen as the optimized desorption time for further experiments. Enrichment factor (EF) study with initial Auramine O concentration of 0.05 ppm is shown in Figure 4B. Across the EFs of 5–50 times, the MIPs material obtained recoveries range from 92.08% to 96.31%, indicating sufficient enrichment capability. However, the recovery began to drop significantly when the enrichment factor exceeded 50 times due to the higher accumulation of Auramine O in the polymer network.

3.4. Reusability of MIPs material

The reusability of MIPs was indicated in Figure 4C. In particular, the adsorption and desorption efficiency of the first five cycles were in the range from 94.12% to 87.68% and from 92.78% to 85.89%, respectively. Overall efficiency tended to decrease after the fifth cycle due to the structural disruption of the polymer network, directly transforming the morphology of adsorption sites. The consistent adsorption–desorption process may cause network fracturing and micro pore collapse, which destabilize interactions within the structure of MIPs [44]. Overall, the MIP material can be recycled up to five times, providing advantageous features for further applications like preconcentration and sample preparation.

3.5. Adsorption selectivity

Adsorption selectivity of the imprinted material (MIPs) with Auramine O (Figure 4D) was evaluated via adsorption experiments with other noteworthy dyes from several groups or in the presence of different electrolytes. The experiments were conducted with a material content of 2.0 mg mL-1 dispersed in various 10.0 mL dye standard solution of 10.0 ppm, which consists of: Quinoline Yellow (QL Y), Tartrazine (TAR), Sunset Yellow (SS Y), Leuco Malachite Green (LMG), Chrysodine (CHR), Malachite Green (MG), and Auramine O (AO).

Figure 4. (A) Study of desorption duration; (B) Enrichment factor investigation; (C) Reusability of MIPs; (D) Adsorption selectivity of MIPs (n = 3).

It was witnessed that the adsorption efficiency of MIPs toward Auramine O achieved 95.57%, superior to other yellow dyes, including QL Y, TAR and SS Y, of which efficiency only fluctuated in the range of 5.72–32.05%. The obtained result can be explained by the presence of specific functional groups. For instance, three of them contain several sulfonic acid groups, whereas Tartrazine also consists of one carboxyl group, which negatively charges the overall molecule under neutral pH [45]. Meanwhile, MIPs is functionalized by MAA, which is a carboxylic acid, likewise, obtaining negative charges [46]. Therefore, strong repulsion between MIPs and the mentioned anionic yellow dye can be deduced, directly destabilizing the interaction and decreasing adsorption efficiency. In terms of chemical adsorption, this result proved the notable selectivity of MIPs to Auramine O among other dyes with similar color.

However, regarding the dyes such as Chrysodine (reddish orange), Leuco Malachite Green (pale green), and Malachite Green (bluish green), which originally consist of positive charges at amino groups and conjugated systems like Auramine O, higher adsorption efficiency was obtained in the range of 49.44% to 76.79%. Although selective adsorption of Auramine O among other dyes can be witnessed, this data indicates that the non-specific binding of structurally similar compounds to Auramine O can feasibly occur, altering the selectivity of MIP material.

Likewise, the selectivity of Auramine O adsorption was assessed in the presence of 50.0 ppm of different electrolytes such as NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, and CaCl2. A maintenance of high adsorption efficiency of MIPs towards Auramine O can be observed, deducing minor suppression from the ionic environment. This favourable feature of MIPs promises further advantages in real sample preparation, particularly without excessive dilution or other treatments.

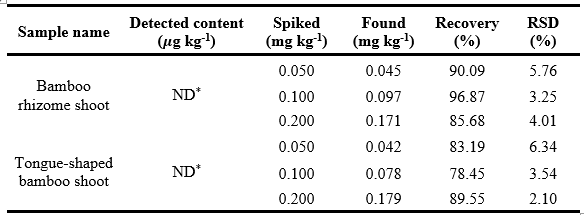

3.6. Real sample analysis

For the quantification of Auramine O in bamboo shoot matrices, the analytical performance of the sonication-assisted extraction method and preconcentration using MIPs was systematically examined in Table 3. Auramine O's absence in unspiked samples (ND) verified the method's reliability and absence of contamination. To assess the accuracy of the approach, recovery studies were carried out at three spiking levels (0.050, 0.100, and 0.200 mg/kg) which were replicated 3 times for each sample. According to the AOAC guidelines for single-laboratory validation of chemical methods, recoveries between 80% and 110% are recommended for reliable residue analysis [47]. The obtained recovery values, which ranged from 78.45% to 96.87%, are consistent with these criteria.

Table 3. The Auramine O detection results in bamboo shoot samples (n = 3).

* ND: Non-detected

With values ranging from 2.10% to 6.34%, precision was evaluated using relative standard deviation (RSD), which is significantly lower than the upper limits suggested by both AOAC guidelines (<15%)[47]. Such low RSD values demonstrate that the extraction and analytical process is highly robust and reproducible across a range of sample types and concentration levels. When considered as a whole, these validation parameters demonstrate that the acidified ethanol-water solvent system, in combination with the sonication-assisted extraction method, offers a reliable, accurate, and efficient method for determining Auramine O in complex plant matrices. This technique represents a practical and reliable alternative to conventional extraction methods, while facilitating routine monitoring and enforcement against the illegal use of prohibited dyes in food products.

3.7. Current limitations and future work

This study was confined to batch-by-batch adsorption experiments, and the large-scale or continuous operation of the synthesized MIPs has not yet been explored. The selectivity assessment was conducted using a limited range of structural analogs, which may not fully represent the complexity of real environmental or food matrices. Moreover, the column-mode solid-phase extraction (SPE) configuration has not yet been implemented or systematically evaluated.

Future research will focus on integrating the developed MIPs into column-based SPE systems to enable automated and continuous operation with enhanced efficiency and reproducibility. Further studies will also aim to apply the material for the determination of Auramine O in various water samples, assessing its performance in real environmental conditions. In addition, optimization of the polymer composition and detection strategy will be pursued to advance the analytical sensitivity and achieve lower limits of detection suitable for trace-level monitoring.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) were successfully synthesized via precipitation polymerization, combined with UV-Vis spectroscopy for the trace detection of Auramine O in food products. Prepared MIPs exhibit an excellent maximum adsorption capacity of 125.521 mg g⁻¹, a mesoporous structure with the surface area of 336.31 m2 g-1 and an imprinted factor (IF) of 2.77. Precipitation polymerization was proved to be a simple and efficient approach for MIP synthesis, though slight variations in particle size and binding site distribution may affect batch reproducibility. With proper optimization, these effects can be minimized for consistent performance. The material was effectively applied for the preconcentration of Auramine O in bamboo shoot samples, achieving high recovery rates (78.45%–96.87%) with RSDs below 7% and enabling a 50-fold enrichment for ppb-level detection of Auramine O. The reusability of MIPs was demonstrated to reach up to 5 efficient adsorption-desorption cycles, indicating the potential application of Auramine O removal in waste-water samples. This study highlights the potential of the MIP material for further development into solid-phase extraction columns and its application across various analytical platforms such as electrophoresis, HPLC, and electrochemical methods, as well as in the analysis of other food and environmental matrices.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Science, Vietnam National University, for providing access to laboratory facilities and continuous support throughout the course of this research.

Author contributions: Nguyen Thi Phuong Anh, Tran Dong Duong, Phan Thi Thanh Thuy: Investigation & Experimentation; Writing - Original Draft; Nguyen Tuan Minh: Data curation; Luu Thi Huyen Trang, Vu Thi Trang, Nguyen Thi Anh Huong: Formal Analysis; Nguyen Thi Phuong Anh, Pham Thi Ngoc Mai: Conceptualization & Methodolody; Pham Thi Ngoc Mai: Supervision and Correspondence.

Conflicts of interest statement: The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

2 J. Liu et al., Fabrication of novel immobilized and forced Z-scheme Ag|AgNbO3/Ag/Er3+:YAlO3@Nb2O5 nanocomposite film photocatalyst for enhanced degradation of auramine O with synchronous evolution of pure hydrogen, Sep Purif Technol, Vol. 288, No. December 2021, p. 120658, 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120658

3 W. Wang et al., Paper-based visualization of Auramine O in food and drug samples with carbon dots-incorporated fluorescent microspheres as sensing element, Food Chem, Vol. 429, p. 136890, Dec. 2023. DOI: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2023.136890

4 W. Yang, T. Muhammad, A. Yigaimu, K. Muhammad, and L. Chen, Preparation of stoichiometric molecularly imprinted polymer coatings on magnetic particles for the selective extraction of Auramine O from water, J Sep Sci, Vol. 41, No. 22, pp. 4185–4193, Nov. 2018. DOI: 10.1002/JSSC.201800797

5 Z. Gholami, K. Yetilmezsoy, and M. H. Ahmadi Azqhandi, Development of a magnetic nanocomposite sorbent (NiCoMn/Fe3O4@C) for efficient extraction of methylene blue and Auramine O, Chemosphere, Vol. 355, p. 141792, May 2024. DOI: 10.1016/J.CHEMOSPHERE.2024.141792

6 D. Vecchio et al., DNA Fragmentation and sister chromatid exchanges induced by commercial Auramine O, Purified Auramine, and Michler’s Ketone, The Use of Human Cells for the Evaluation of Risk from Physical and Chemical Agents, pp. 745–754, 1983. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4757-1117-2_43

7 IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Chemical agents and related occupations, IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012, Vol. 100, No. Pt F, pp. 9–562.

8 T. T. Tran-Lam, M. B. T. Hong, G. T. Le, and P. D. Luu, Auramine O in foods and spices determined by an UPLC-MS/MS method, Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 171–176, Jul. 2020. DOI: 10.1080/19393210.2020.1742208

9 D. T. N. Hoa et al., Voltammetric determination of Auramine O with ZIF-67/Fe2O3/g-C3N4-modified electrode, Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, Vol. 31, No. 22, pp. 19741–19755, Nov. 2020. DOI: 10.1007/S10854-020-04499-W/METRICS

10 C. Tatebe, X. Zhong, T. Ohtsuki, H. Kubota, K. Sato, and H. Akiyama, Unauthorized basic colorants (rhodamine B, auramine O, and pararosaniline) in processed foods determined by a simple and rapid chromatographic method, Food Sci Nutr, Vol. 2, No. 5, pp. 547–556, Sep. 2014. DOI: 10.1002/FSN3.127

11 A. Al Tamim, M. AlRabeh, A. Al Tamimi, A. AlAjlan, and A. Alowaifeer, Fast and simple method for the detection and quantification of 15 synthetic dyes in sauce, cotton candy, and pickle by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, Arabian Journal of Chemistry, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 3882–3888, Feb. 2020. DOI: 10.1016/J.ARABJC.2019.09.008

12 M. E. I. Badawy, M. A. M. El-Nouby, P. K. Kimani, L. W. Lim and E. I. Rabea, A review of the modern principles and applications of solid-phase extraction techniques in chromatographic analysis, Analytical Sciences 2022 38:12, Vol. 38, No. 12, pp. 1457–1487, Oct. 2022. DOI: 10.1007/S44211-022-00190-8

13 M. Mahdavijalal, C. Petio, G. Staffilano, R. Mandrioli, and M. Protti, Innovative Solid-Phase Extraction Strategies for Improving the Advanced Chromatographic Determination of Drugs in Challenging Biological Samples, Molecules 2024, Vol. 29, Page 2278, Vol. 29, No. 10, p. 2278, May 2024. DOI: 10.3390/MOLECULES29102278

14 M. M. Sabzehmeidani, S. Mahnaee, M. Ghaedi, H. Heidari, and V. A. L. Roy, Carbon based materials: a review of adsorbents for inorganic and organic compounds, Mater Adv, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 598–627, Feb. 2021. DOI: 10.1039/D0MA00087F

15 C. Cheng, W. Song, Q. Zhao and H. Zhang, Halloysite nanotubes in polymer science: Purification, characterization, modification and applications, Nanotechnol Rev, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 323–344, Jan. 2020. DOI: 10.1515/NTREV-2020-0024

16 L. Ma, Y. Qiang and W. Zhao, Designing novel organic inhibitor loaded MgAl-LDHs nanocontainer for enhanced corrosion resistance, Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 408, p. 127367, Mar. 2021. DOI: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2020.127367

17 R. Si et al., Nanoarchitectonics for high adsorption capacity carboxymethyl cellulose nanofibrils-based adsorbents for efficient Cu2+ removal, Nanomaterials 2022, Vol. 12, No. 1, p. 160, Jan. 2022. DOI: 10.3390/NANO12010160

18 A. Martín-Esteban, Molecularly imprinted polymers: Selective extraction materials for sample preparation, Separations, Vol. 9, No. 5, May 2022. DOI: 10.3390/SEPARATIONS9050133

19 A. Poliwoda, M. Mościpan and P. P. Wieczorek, Application of molecular imprinted polymers for selective solid phase extraction of Bisphenol A, Ecological Chemistry and Engineering S, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 651–664, Dec. 2016. DOI: 10.1515/ECES-2016-0046

20 M. S. Kang, E. Cho, H. E. Choi, C. Amri, J. H. Lee and K. S. Kim, Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs): emerging biomaterials for cancer theragnostic applications, Biomaterials Research 2023 27:1, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 1–32, May 2023. DOI: 10.1186/S40824-023-00388-5

21 M. B. Khawar, A. Afzal, M. M. Ali, and H. Sun, A novel approach for tumor-released Methylated DNA detection using molecularly imprinted polymers, Adv Funct mater, Vol. 34, No. 45, p. 2405786, Nov. 2024. DOI: 10.1002/ADFM.202405786

22 Z. Gao et al., Molecularly imprinted polymers for highly specific bioorthogonal catalysis inside cells, Angewandte chemie - International edition, Vol. 63, No. 49, p. e202409849, Dec. 2024. DOI: 10.1002/ANIE.202409849

23 E. Mutlu, A. Şenocak, E. Demirbaş, A. Koca and D. Akyüz, Selective and sensitive molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensor for detection of deltamethrin, Food Chem, Vol. 463, p. 141121, Jan. 2025. DOI: 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2024.141121

24 Y. Saylan, Ö. Altıntaş, Ö. Erdem, F. Inci and A. Denizli, Overview of molecular recognition and the concept of MIPs, Molecularly imprinted polymers as artificial antibodies for the environmental health, pp. 1–29, 2024. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-58995-9_1

25 M. A. Al-Ghouti, D. A. Da’ana, Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review, J Hazard Mater, Vol. 393, p. 122383, Jul. 2020. DOI: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2020.122383

26 K. Y. Foo, B. H. Hameed, Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems, Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 156, No. 1, pp. 2–10, Jan. 2010. DOI: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2009.09.013

28 Y. L. Mustafa, H. S. Leese, Fabrication of a lactate-specific molecularly imprinted polymer toward disease detection, ACS Omega, Vol. 8, No. 9, pp. 8732–8742, Mar. 2023. DOI: 10.1021/ACSOMEGA.2C08127

29 R. M. Roland, S. A. Bhawani and M. N. M. Ibrahim, Synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymer for the removal of cyanazine from aqueous samples, Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 1–19, Dec. 2023. DOI: 10.1186/S40538-023-00462-Z/TABLES/7

30 T. Jing et al., Preparation of high selective molecularly imprinted polymers for tetracycline by precipitation polymerization, Chinese Chemical Letters, Vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1535–1538, Dec. 2007, doi: 10.1016/J.CCLET.2007.10.029

31 K. Haupt, A.-S. Belmont, Molecularly imprinted polymers as recognition rlements in sensors, Handbook of Biosensors and Biochips, Jul. 2007. DOI: 10.1002/9780470061565.HBB020

32 Molecularly Imprinted Polymers as artificial antibodies for the environmental health, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers as Artificial Antibodies for the Environmental Health, 2024. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-58995-9

33 B. Fresco-Cala, A. D. Batista, and S. Cárdenas, Molecularly imprinted polymer micro- and nano-particles: A review, Molecules 2020, Vol. 25, No. 20, p. 4740, Oct. 2020. DOI: 10.3390/MOLECULES25204740

34 N. P. Kalogiouri, A. Kabir, K. G. Furton and V. F. Samanidou, A tutorial on the synthesis and applications of molecularly imprinted polymers in analytical chemistry, Journal of Chromatography Open, Vol. 8, p. 100244, Nov. 2025. DOI: 10.1016/J.JCOA.2025.100244

35 R. Fathi Til, M. Alizadeh-Khaledabad, R. Mohammadi, S. Pirsa and L. D. Wilson, Molecular imprinted polymers for the controlled uptake of sinapic acid from aqueous media, Food Funct, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 895–906, Jan. 2020. DOI: 10.1039/C9FO01598A

36 T. Aydan, J. J. Yang, T. Muhammad, F. Gao, X. X. Yang and Y. T. Hu, In-situ measurement of Auramine-O adsorption on macroporous adsorption resins at low temperature using fiber-optic sensing, Desalination Water Treat, Vol. 213, pp. 240–247, Feb. 2021. DOI: 10.5004/DWT.2021.26675

37 N. Khatri, S. Tyagi and D. Rawtani, Removal of basic dyes auramine yellow and auramine O by halloysite nanotubes, Int J Environ Waste Manag, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 44–59, 2016. DOI: 10.1504/IJEWM.2016.076427

38 M. Firoozi, Z. Rafiee and K. Dashtian, New MOF/COF Hybrid as a robust adsorbent for simultaneous removal of Auramine O and Rhodamine B dyes, ACS Omega, Vol. 5, No. 16, pp. 9420–9428, Apr. 2020. DOI: 10.1021/ACSOMEGA.0C00539

39 S. chaudhary, J. Sharma, B. S. Kaith, S. yadav, A. K. Sharma and A. Goel, Gum xanthan-psyllium-cl-poly(acrylic acid-co-itaconic acid) based adsorbent for effective removal of cationic and anionic dyes: Adsorption isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic studies, Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, Vol. 149, pp. 150–158, Mar. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.11.030

40 A. Asfaram, M. Ghaedi, S. Hajati, M. Rezaeinejad, A. Goudarzi and M. K. Purkait, Rapid removal of Auramine-O and Methylene blue by ZnS:Cu nanoparticles loaded on activated carbon: A response surface methodology approach, J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng, Vol. 53, pp. 80–91, Aug. 2015. DOI: 10.1016/J.JTICE.2015.02.026

41 M. Abdolhosseinzadeh, S. J. Peighambardoust, H. Erfan-Niya and P. Mohammadzadeh Pakdel, Swelling and auramine-O adsorption of carboxymethyl cellulose grafted poly(methyl methacrylate)/Cloisite 30B nanocomposite hydrogels, Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition), Vol. 27, No. 10, pp. 807–818, Oct. 2018. DOI: 10.1007/s13726-018-0654-1

42 P. Pataer et al., Preparation of a stoichiometric molecularly imprinted polymer for auramine O and application in solid-phase extraction, J Sep Sci, Vol. 42, No. 8, pp. 1634–1643, Apr. 2019. DOI: 10.1002/JSSC.201801234

43 A. Kütt et al., Strengths of acids in acetonitrile, European J Org Chem, Vol. 2021, No. 9, pp. 1407–1419, Mar. 2021. DOI: 10.1002/EJOC.202001649

44 S. Mohebbi, A. D. Khatibi, D. Balarak, M. Khashij, E. Bazrafshan and M. Mehralian, Endocrine disruptor (17 β-estradiol) removal by poly pyrrole-based molecularly imprinted polymer: kinetic, isotherms and thermodynamic studies, Appl Water Sci, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 1–13, Feb. 2025. DOI: 10.1007/S13201-025-02373-W/TABLES/6

45 J. F. Senackerib, Color additives for foods, drugs, and cosmetics, Colorants for Non-Textile Applications, pp. 131–188, 2000. DOI: 10.1016/B978-044482888-0/50035-0

46 S. Roy et al., Recent advances in bioelectroanalytical sensors based on molecularly imprinted polymeric surfaces, Multifaceted Bio-sensing Technology: Bioelectrochemical Systems: the way forward, Vol. IV, pp. 111–134, Jan. 2022. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90807-8.00009-9

47 Vishalli, R. Kaur, K. K. Raina and K. Dharamvir, Investigation on single walled carbon nanotube thin films deposited by langmuir blodgett method, AIP Conf Proc, Vol. 1661, pp. 1–38, 2015. DOI: 10.1063/1.4915424